Renters burdened by unaffordable housing costs may be at a higher risk of dying sooner, according to a new study published in the journal Social Science & Medicine.

An individual paying 50% of their income toward rent in 2000 was 9% more likely to die over the next 20 years compared with someone paying 30% of their income toward rent, according to the study from researchers at Princeton University and the U.S. Census Bureau’s Center for Economics Studies. Someone paying 70% of their income toward rent, meanwhile, was 12% more likely to die.

“We were surprised by the magnitude of the relationship between costs and mortality risk,” said Nick Graetz, a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University and the study’s lead author. “It’s an especially big problem when we consider how many people are affected by rising rents. This isn’t a rare occurrence.”

More from Personal Finance:

Even high earners consider themselves ‘not rich yet’

Credit card debt is ‘the biggest threat to building wealth’

Americans are ‘doom spending’

Rising rents have far outpaced wages, leaving the typical renter in the U.S. paying 30% or more of their income for housing. In 2019, 4 in 5 renter households with incomes below $30,000 were rent-burdened.

The Princeton researchers collaborated with the Census Bureau to create a dataset that allowed them to follow individual renters from 2000 on. They analyzed millions of records to understand the link between rent burden, eviction and mortality for people.

In addition to the consequences of unaffordable rent, they found that even being threatened with eviction was associated with a 19% increase in mortality. Receiving an eviction judgment was associated with a 40% increase in the risk of death.

CNBC interviewed Graetz about the study findings. The interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

‘As rents go up, families cut back on other spending’

Annie Nova: What is it about being rent burdened that increases mortality?

Nick Graetz: We know housing is the primary cost for American families, and as rents go up, families cut back on other spending, including on essentials that affect their health.

For example, poor households with children who are moderately rent-burdened, devoting 30% to 50% of their income to rent, spend 57% less on healthcare and 17% less on food compared to similar unburdened households.

AN: Why is eviction, even more than being rent burdened, linked to higher mortality?

NG: Eviction is a really traumatic event that leads to disenrollment from social safety net programs, such as Medicaid. It can also lead to job loss and a host of other negative consequences.

Eviction can compromise a person’s physical and mental health by exposing them to prolonged periods of intense housing precarity, including homelessness and acute stress.

In addition, eviction can increase exposure to infectious disease, as seen during the Covid-19 pandemic. Even just having an eviction filing on your record can limit your ability to secure future safe and stable housing, which can have impacts on health outcomes.

Current system makes it ‘difficult to retain housing’

AN: What efforts for change do you hope to see in response to your findings?

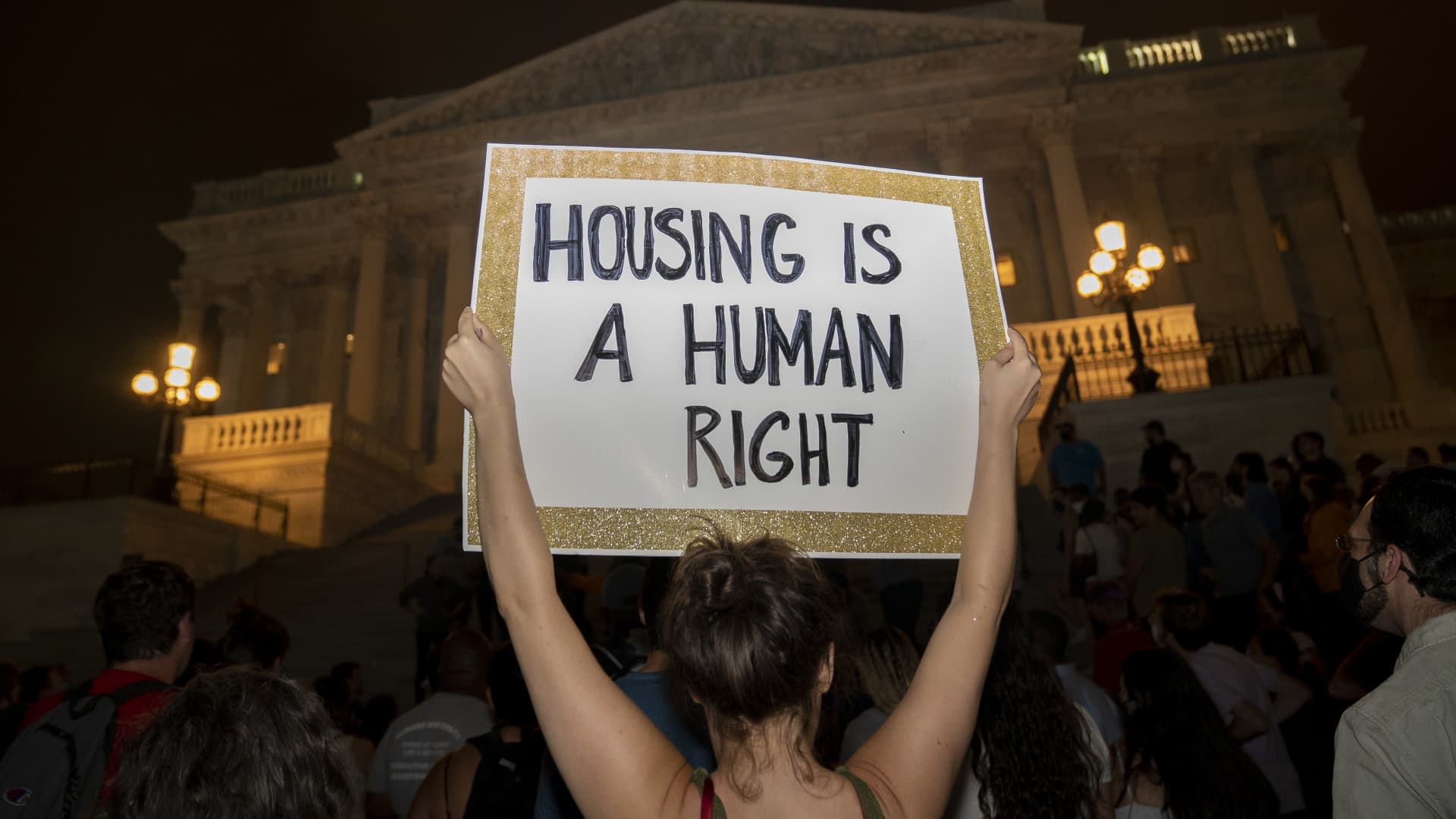

NG: We demonstrate in this new paper that as rent burdens hit record highs today, we should be considering policies to reduce evictions and guarantee affordable housing as not just housing policy, but as critical health policy.

In general, we live under a system that makes it really difficult to retain our housing whenever we experience a problem. A sudden health issue in your family, a car crash or any other unexpected problem can lead to an eviction in a short time.

It’s especially important to act now: eviction filings are increasing in every city and state that we track.

AN: Are there any policies currently in effect that are making the problem better?

NG: Across the U.S., cities and states are trying different and sometimes overlapping policies to promote housing stability and avoid evictions.

Some important legal aid programs include the right to counsel. When tenants are provided legal counsel, the odds of them remaining in their homes increase dramatically. Under New York City’s right to counsel in eviction court, 84% of represented renters facing eviction remain housed. In Cleveland, 93% of represented renters facing eviction avoid displacement.

Many states and cities, such as Rhode Island and DC, are considering programs like rent control and social housing, characterized by being mixed-income, mixed-use and with more resident involvement in governance than traditional public housing.

We need to create a country where quality housing is affordable to everyone.

Don’t miss these stories from CNBC PRO: